Even before the Waste to Zero initiative was launched at the COP28 Climate Change conference in December 2023, an inspiring group of women in Dar es Salaam have been spearheading an approach that is tackling the waste crisis in the city by transforming waste into opportunities.

The women are members of a cooperative in Kimara which collects, sorts and repurposes waste for recycling. The Kimara women’s cooperative is a member of Nipe Fagio (give me a broom in Kiswahili), an initiative started ten years ago to address the problem of waste management in the city.

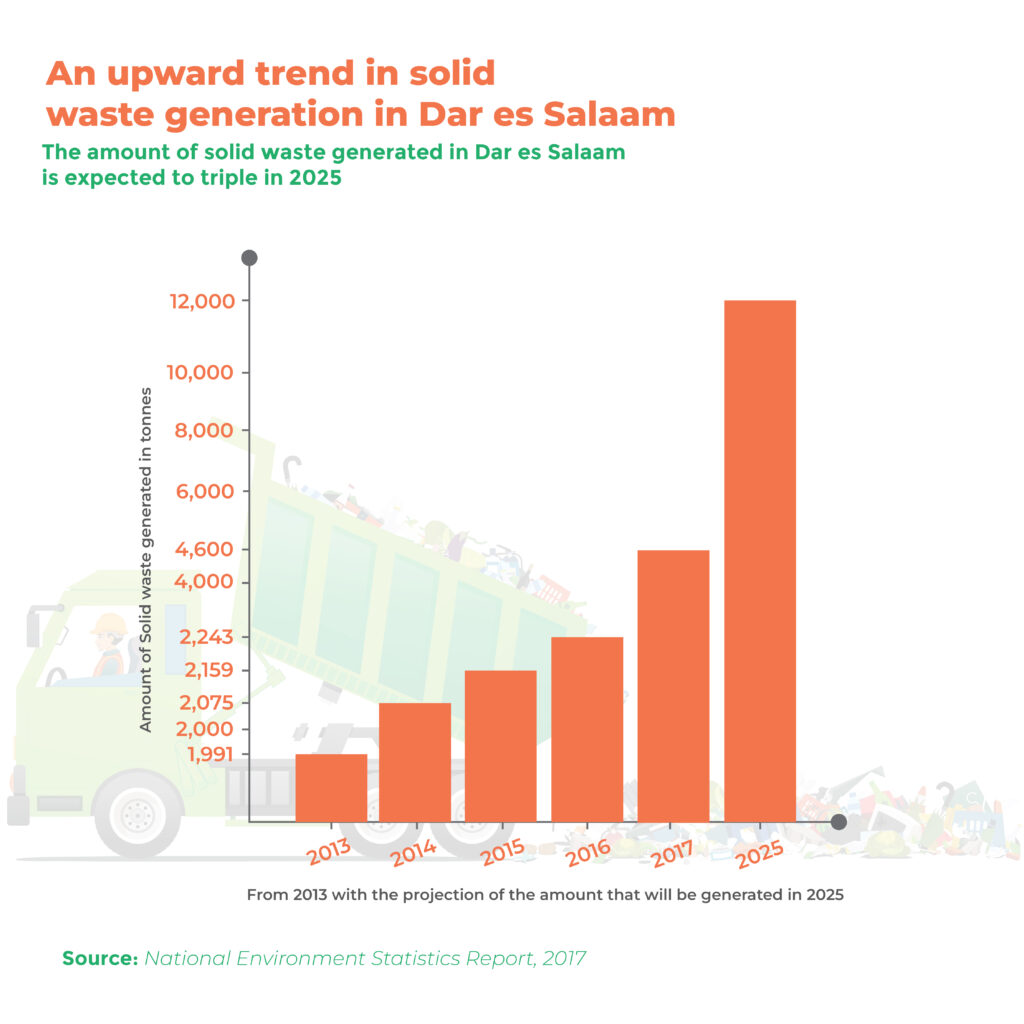

It is estimated that the city produces over 5,600 tonnes of waste daily. Less than 40 per cent of this waste is collected. When it is collected, it is all mixed up and ends up in one location— the Pugu Kinyamwezi dumpsite, located nearly 35 kilometres from the city centre. The dumpsite was planned to be constructed as an engineered landfill site with all the pollution control mechanisms in place in the mid-2000s.

However, due to funding constraints, these plans failed at the construction and resulted in what it is today – an open dumping site without any fencing, barrier layers, soil cover, leachate and gas collection or treatment systems. Most of the garbage is either dumped illegally, buried or burnt and when it rains, it clogs the waterways, contaminates soil and increases urban air pollution. Open dumping of solid waste is a major health and environmental threat to communities surrounding city dump sites.

Numerous studies have shown the severe impacts of open dumping of solid waste on the environment, public health and climate change. It includes soil degradation and contamination of water sources as hazardous chemicals leach into the ground. This, in turn, disrupts ecosystems and poses a threat to biodiversity.

Open dumps become breeding grounds for disease vectors, leading to the spread of infectious diseases such as cholera and respiratory illnesses, especially among communities living near such dumpsites who are exposed to harmful toxins and pollutants. Additionally, the release of methane, a potent greenhouse gas that is even more dangerous than carbon dioxide, from decomposing organic matter in open dumpsites, significantly contributes to climate change, worsening global warming.

An August 2023 report by the Global Climate and Health Alliance said landfills and wastewater make up about 20 per cent of global anthropogenic emissions. Anthropogenic emissions are pollutants or substances released into the air, water, or soil as a result of human activities. These emissions come from various human-related sources such as factories, vehicles, power plants, and other industrial processes.

Examples of anthropogenic emissions include carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels, pollutants from industrial processes, and waste disposal. Essentially, anthropogenic emissions are human-made contributions to environmental pollution.

Reducing human-caused methane emissions by as much as 45 per cent, or 180 million tonnes a year by 2030 will avoid nearly 0.3°C of global warming by the 2040s.

“It would also prevent 255,000 premature deaths, 775,000 asthma-related hospital visits, 73 billion hours of lost labour from extreme heat, and 26 million tonnes of crop losses globally, every year,” according to this report by UNEP.

Climate change impacts are not “gender neutral” as women and girls experience disproportionate challenges from climate change. They depend more on, yet have less access to, natural resources. In Tanzania, like many other regions in the world, women bear a disproportionate responsibility for securing food, water, and fuel. Women, as agricultural workers and primary procurers, work harder to secure income and resources for their families.

According to a paper by the World Bank, in poor households, for every 100 poor men aged 25 to 34 years, there are 122 poor women in the same age group, with countries in Africa having the largest gender poverty gap.

In urban areas, such as Dar es Salaam, households headed by women have a 20 per cent poverty rate, compared to a 14 per cent poverty rate in households headed by men, notes a World Bank analysis. Moreover, there’s a gender gap in agricultural food production, mostly explained by a lack of access to male labour. Access to farm inputs also plays a part. Women are also more likely than men to do unpaid work, and where they are paid, they earn less than men in similar roles.

It is in this context that the women of Kimara came together to see what they could do to address some of these challenges and at the same time, contribute to the wellbeing of their communities.

Rehema Tamimu, chairperson of the cooperative recounts how she and other women decided to come together to not only make their environment clean but also make money out of waste.

“There used to be waste thrown all over the place. The mounds of garbage would stink, but we did not know what to do. When it was collected, it was just dumped. That is when we reached out to Nipe Fagio for help on how to deal with the problem,” she says.

This training opened their eyes to the potential of waste as a valuable resource.

“After getting the training and seed funding from Nipe Fagio institution, we are making money out of waste,” she adds.

Nipe Fagio provided the women with training on the impact of waste on their environment, and how to safely separate garbage for recycling.

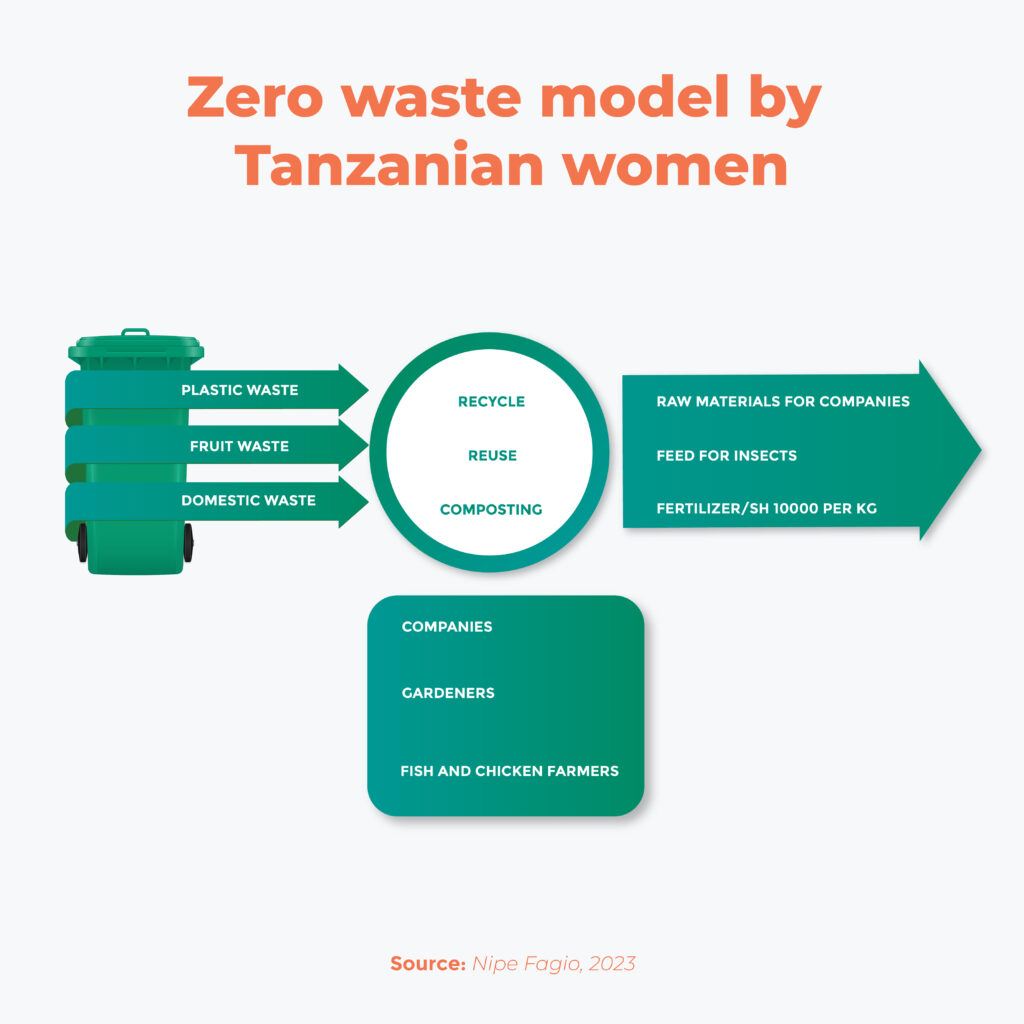

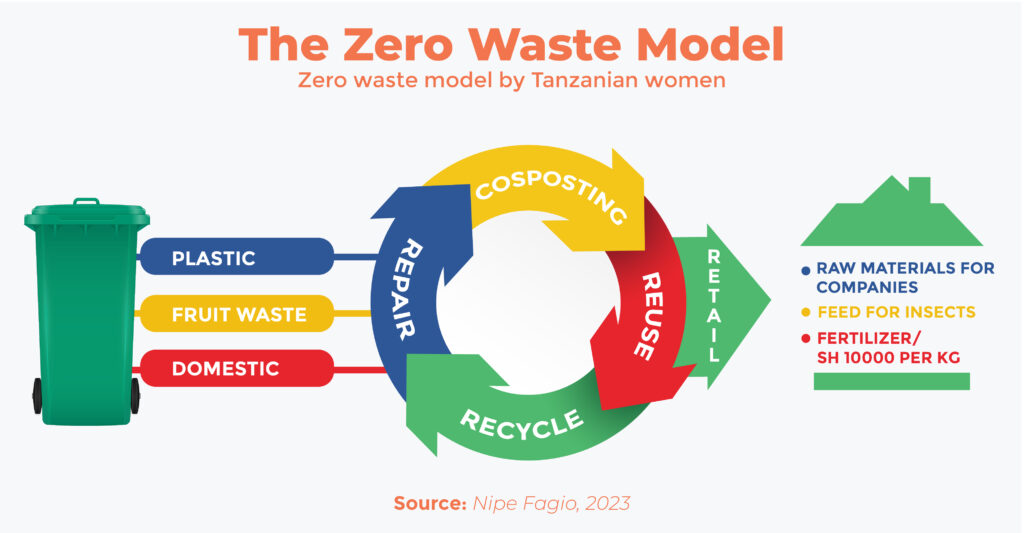

The women collect the garbage from households in their neighbourhood, then store it at a decentralised centre where it is sorted and separated into four categories —organic, recyclable and domestic hazardous waste. Organic waste is kitchen waste such as vegetables, fruits, and leaves, while toxic or domestic hazardous waste includes such things as batteries, paint, old medicines and other chemicals. Recyclable waste includes glass, cardboard, paper, plastics and metals.

Halima Muda, a member of the cooperative proudly explains how she and other members sort and segregate the waste for sale. Plastic waste is sold for recycling. The plastic waste is sorted according to density, melted and then mixed with sand to produce bricks, paving blocks or tiles which have been used for the construction of affordable housing, public toilets and other buildings, especially in rural areas.

Organic waste is transformed into fertiliser, which is sought after by gardeners. The women sell the organic fertiliser at Sh10,000 per kilogramme. The fruit waste is fed to black soldier flies whose larvae are used as feed by chicken and fish farmers. The women sell the larvae at Sh5,000 per kilogramme. The Dar es Salaam city centre and Nipe Fagio provide the women’s cooperative with market connections to sell their products.

Halima also highlights the “double profit” generated by their initiative. They make money from collecting waste from households. For this service, they charge each household between Sh2,000 to Sh5,000 per month. They also make money from processed materials i.e. fertiliser and from the sale of recyclable waste such as plastics, paper, wood and other such products which are recycled into other products. The co-operative makes Sh800,000 on average which is then shared among the members. They retain a percentage of their earnings which is then given out as loans and also to cater for their operational costs and taxes.

The initiative has transformed the lives of women and their families as they are not only employed but can also count on having money to meet their basic needs. Halima says the cooperative has transformed her life. Her weekly income has quadrupled since she joined the cooperative. She previously earned an average of Sh10,000 per week from collecting garbage from peoples’ homes but she currently makes between Sh40,000 to Sh50,000 per week because she ‘adds value’ by processing the organic waste into fertiliser and animal feed.

Halima, who is a single mother of three, relishes her newfound financial stability which has enabled her to meet her family’s needs such as school fees and other essentials and also save some money.

“This is something I never thought I would be able to do. Open an account and save money!” Halima says.

Her colleague, Anusiata Mapunda has opened a side business where she is raising chicken for eggs and meat. The extra income she makes from the business and the stability of having a regular income from the waste processing job means she is now able to pay school fees for her only child who is attending a government school.

“Before I used to collect only Sh10,000 per week, but since I joined this group and started selling bottles and making fertilisers and fish food, I earn Sh50,000 to Sh60,000. I can afford to pay for my son’s fee of Sh300,000 per year at the government English school,” she said.

The women not only earn a stable income but also contribute to keeping the streets clean and reducing health risks associated with waste mismanagement.

Waste picking is not considered to be ‘decent’ work, particularly for women. Since waste picking is predominately conducted by men, the members of the Kimara Waste Pickers Cooperative Society face unique challenges. These range from lack of modern work tools, health hazards during waste collection, and societal stigma. They also often face negative perceptions from the community, hindering their participation in waste management activities.

“Sometimes people think we are mentally unstable or are thieves and this makes our work of collecting garbage difficult,” says Sauda Salum.

“When people see us wearing dirty clothes and no identification mark for the work we do, they think we are strange or weird. There was a day when I went out to collect waste from a household and they thought I was a thief because of how I looked—dirty clothes and all. If we had proper equipment, especially protective clothing, we could avoid some of these challenges,” Sauda adds.

To create awareness about the essential services they provide, the women teach households how to separate their waste. They also provide them with different baskets or containers to keep the waste separate. This makes it easier for the women to collect and sort the garbage for recycling or processing.

Nipe Fagio also conducts community awareness campaigns and encourages them to sort their waste. Wilyhard Shishikaye, Nipe Fagio’s Zero Waste System Coordinator, explains that the organisation provides both technical and financial assistance to the cooperative.

“Our goal is to empower communities to manage their waste effectively and contribute to a cleaner and healthier environment,” says Shishikaye.

Nipe Fagio conducts house-to-house education sessions on street waste collection and encourages residents to actively sort their waste into different categories: organic, recyclable, and hazardous.

Nipe Fagio also has decentralised material waste processing facilities where the collected waste— particularly hazardous household waste, is treated. Other recyclable waste such as paper, glass and plastic is also collected at these facilities for onward distribution to the recycling firms.

Shishikaye envisions a future where this zero waste system becomes part of the national strategy on solid waste management.

“Imagine every street equipped with this infrastructure, diverting waste from landfills and transforming it into valuable resources and providing employment!”

Nipe Fagio‘s ambition extends beyond the capital city. The organisation has already replicated the system in Zanzibar and Arusha, with plans to expand to other regions across the country.

Shishikaye notes that the government has already shown interest in the Nipe Fagio model. Through the Regional and Local Governments (TAMISEMI), they have invited the organisation to share its knowledge and expertise, paving the way for wider implementation.

The head of the Ilala District Waste Management and Cleaning Department, Rajabu Ngoda says their education and public awareness campaigns are geared towards making people see waste management opportunities instead of seeing waste collection as a burden.

To encourage more people to exploit these opportunities, the government provides loans— usually with a repayment of 10 per cent interest— to interested youth groups, women and people living with disabilities. The funds are to help the waste pickers buy protective equipment and set up their waste processing such as fertiliser and animal feeds.

Sub-national governments and local authorities and municipalities are, under the Environmental Management Act of 2004, responsible for the collection, storage, sorting and transportation of waste to achieve the zero waste goals set out by the National Environmental Conservation and Management Council (NEMC).

However, most of the waste produced in the country is not managed and continues to pose a threat to the environment and present public health concerns.

“For example, at least 96 per cent, or about 319,000 tonnes, of the plastic waste produced in Tanzania annually is not managed. This is despite the ban on single-use plastic bags,” says Natural Resources and Environment Conservation Officer of the Dar es Salaam City Council Enock Tumbo.

He says community-driven waste management initiatives such as Nipe Fagio are important in bridging this gap. The council is also considering setting up a landfill site with pollution control mechanisms to partially address the problem of waste management.

The Waste to Zero initiative, as exemplified by the women of Kimara, not only addresses environmental and health challenges but also provides a sustainable solution to waste management. The success of this initiative highlights the transformative power of community-driven waste management, offering a model that can be replicated nationally to achieve cleaner and healthier environments. As we envision a future where waste becomes a valuable resource, the stories of these women serve as inspiration, emphasising the potential for positive change through innovative and community-driven solutions.

I love how this blog gives a voice to important social and political issues It’s important to use your platform for good, and you do that flawlessly

perferendis at cum nihil magnam velit quis consectetur incidunt saepe et officia eaque placeat veritatis autem placeat vel quod non possimus. saepe minima debitis quasi est quam sit qui quis optio reiciendis possimus qui.

The analysis is like a well-crafted movie—engaging, enlightening, and leaving me thinking long after it’s over.

The breadth of The knowledge is amazing. Thanks for sharing The insights with us.

A breath of fresh air, or what I needed after being suffocated by mediocrity.

The elegance of The prose is like a fine dance, each word stepping gracefully to the next.

Genuinely impressed by The analysis. I was starting to think depth had gone out of style. Kudos for proving me wrong!

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Wonderful blog you have here but I was wanting to know if you knew of any community forums that cover the same topics talked about in this article? I’d really love to be a part of group where I can get feed-back from other knowledgeable individuals that share the same interest. If you have any recommendations, please let me know. Cheers!