Dar es Salaam. Municipal waste collection system, which relies on municipal garbage trucks or contracted service providers, does not reach all areas.

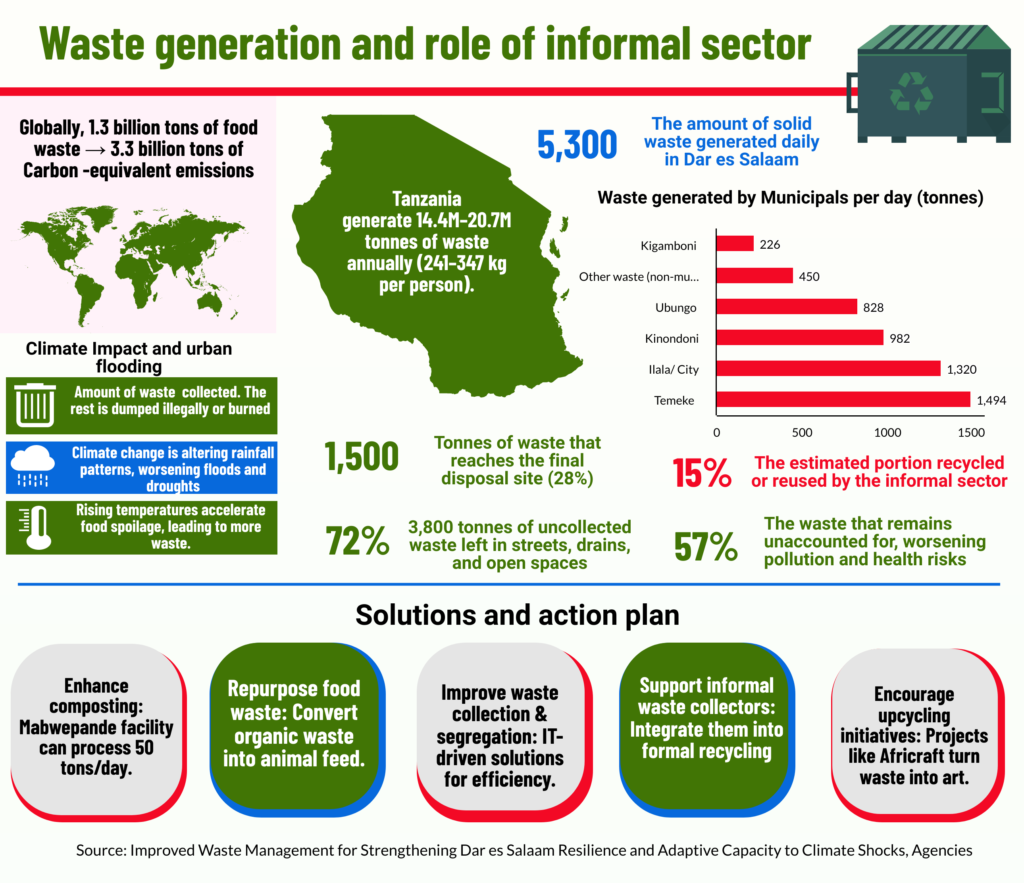

For instance, the Dar es Salaam City Master Plan indicates that the city, with a population of over five million, generates 5,300 tons of mixed solid waste per day from all sources.

A report “Improved Waste Management for Strengthening Dar es Salaam Resilience and Adaptive Capacity to Climate Shocks” cited in the Dar es Salaam Urban Resilience Programme (DURP) found that the final disposal site receives an average of 1,500 tons per day, leaving approximately 3,800 tons uncollected daily—equivalent to 72 percent of the total waste generated.

“This uncollected waste includes quantities separated, recycled, and reused by the informal sector. We estimate this as 15 percent of the total waste generated, thus leaving 57 percent as unaccounted-for waste,” states the DURP report.

An investigation by this publication has found that many urban areas in Dar es Salaam, particularly densely populated neighborhoods with inadequate road infrastructure, face significant waste collection challenges. Examples of such areas include Vingunguti, Manzese, and Msasani.

“Garbage trucks do not reach our area. Even when they do, they stop at the roadside, and that happens only a few times a week. We produce food waste daily, and it cannot wait for weekly collection,” says Mariam Kasim, a resident of Vingunguti – Butiama.

Waste collection in these areas is carried out through different means, including some informal actors. There are plastic waste pickers who also operate in other areas, but here waste pickers collect both organic waste and plastic waste.

Some plastic waste including used bottles, organic waste including remains of food from households, restaurants and food market waste.

“We reach areas where garbage trucks do not,” says Manyango Msula, chairman of a 23-member waste pickers called “Pendezesha Vingunguti.” This group collects both organic and non-organic waste and processes it for resale or recycling.

Msula says they reach over 100 households, food stalls, and vendors daily, collecting more than one ton of organic and non-organic waste. “We sell plastic waste, while organic waste is processed into animal feed, and a small portion is used to produce fertilizer,” he explains.

Highlighting a major challenge, Msula points out that people do not separate waste at the source. “People lack awareness. They mix up waste, and sorting it later is a tedious task,” he elaborates.

“Additionally, we lack sufficient equipment for producing the larvae used as animal feed. During hot weather, the larvae do not reproduce as abundantly as they do in cooler conditions,” he explained how they utilizes organic waste.

Bandita Ambrose, chairman of the Jitegemee Maarifa Group based in Chanika, says they collect waste from individuals who provide them with special bags, as well as from food vendors and other sources. “…We produce larvae (animal feed) and fertilizer. In our setup, the larvae start emerging within 14 days,” she says.

Another group, Tufashanwe, based in Majohe Ilala, is also involved in waste collection. “We collect waste from market stalls, chips vendors, food vendors, and some households,” says Tabu Ally, the head of the 14-member group, which consists entirely of women. Tabu states that they collect over one ton of waste daily and process it into animal feed and fertilizer for sale.

Challenges

Tabu Ally highlighted that the main challenge is poor road infrastructure. “We use a battery-powered tricycle (tuk-tuk) to transport the waste, but it gets damaged when we drive on sandy roads. When it rains, it becomes even more difficult,” she explained.

Manyango Msula pointed out that their group consists of people from diverse backgrounds, including former drug addicts who are still struggling to fully reintegrate into normal life. “Some of them are not yet fit enough, so we have to support and push each other to collect the waste,” he said.

He also mentioned that the lack of public awareness leads to waste being mixed and hence reduces the quality of material and making the sorting process more labor-intensive.

Another major challenge is limited capital, which restricts investment in better waste management practices. “I once had a client who wanted to buy one ton of larvae per day, but we can only produce less than five kilograms. If we had a larger space, we could do so much more,” said Bandita Ambrose.

Experts highlight challenges and opportunities

Sarah Pima, the Director of the Human Dignity and Environment Foundation (HUDEFO), pointed out that financial, technological, and technical limitations are key challenges. “They (informal waste pickers) lack funding and machinery, yet they contribute significantly, but they are not recognized by key institutions,” she said.

She further explained that authorities and policies do not formally recognize waste pickers, which is why efforts are being made to advocate for their recognition. “These small groups consist of people trying to earn a living. They are job seekers,” she elaborated.

On the opportunities side, Sarah emphasized that informal waste collectors play a crucial role in environmental cleanliness and contribute significantly to the waste management value chain.

“Sometimes, without them, even large recyclers wouldn’t function because they rely on materials collected by these workers,” she said.

She noted that while informal waste collectors are starting to gain some recognition, especially those in organized groups, they should be considered for municipal loans and provided with essential resources like machinery and electricity.

“For instance, composting facilities should have heating systems to accelerate decomposition. Also, having grinding machines would ease the process—for example, instead of manually cutting decomposed banana stems, a machine would speed up the process. In some places like Mabwepande ( a large composting plant located in Kinondoni -Dar es Salaam), there are sieving machines that work in minutes, while here, we take long hours,” she explained.

Jennifer Wang, a Partner at Full Cycle Resource Consulting and a Textile Waste and Recycling Consultant with the UNCTAD SMEP Program, pointed out that research in developing countries, including Tanzania, shows that one of the biggest challenges in waste management is the lack of formal recognition of informal waste collectors in national systems and policies.

“This exclusion affects them greatly. There should be separation facilities to make it easier for them to access raw materials (waste), government support, education, funding opportunities, and information development,” she said.

She added that if these measures were implemented, it would ensure the safety of waste collectors while also addressing environmental and health challenges.

Principal Environmental Health Officer for Waste Management and Sanitation at Ilala Municipal Council, Geophrey Zenda pointed out that infrastructure and resources remain a major challenge, as many urban areas lack adequate waste collection systems, recycling facilities, and transportation networks.

However, he notes the challenges of infrastructure and public awareness.

“Recycling must be economically viable. If people separate their waste at the source, it becomes much easier to create valuable products like fertilizers and animal feed,” he explains.

Zenda also stresses the importance of waste separation at the source, as mixed waste complicates processing. “The biggest challenge is people’s perception. Many still view waste collection as a job for the desperate, while in reality, it can provide employment for many,” he concludes.

Обратились за подключением интернета на дачу в области и не пожалели. Специалисты подобрали оптимальный тариф и оборудование. Скорость интернета устраивает полностью. Соединение не обрывается и работает стабильно. Пользуемся с удовольствием https://podklychi.ru/