Nairobi, Kenya. At a UNEA-7 side event titled “High-Integrity Carbon Markets: Impact and Path to Accelerated Climate Action,” held on 9 December at UNEP Headquarters in Nairobi, the United Nations Environment Programme Executive Director Inger Andersen underscored the urgent need to fix and scale carbon markets if the world is to meet its climate goals.

Andersen said recent gains in adaptation finance and efforts to address deforestation are encouraging, but not enough to shift the global trajectory.

Current projections show the world heading toward a temperature rise of 2.3 to 2.5°C by 2100, far beyond the Paris Agreement thresholds. To limit overshoot and return to the 1.5°C pathway, she said, global emissions must fall by 46 percent by 2035.

A big part of the solution, she noted, lies in rapidly expanding climate finance. Adaptation alone will require $310–360 billion annually by 2035, yet current flows remain at around $25 billion. “There is work to be done,” she said, warning that the funding gap continues to widen.

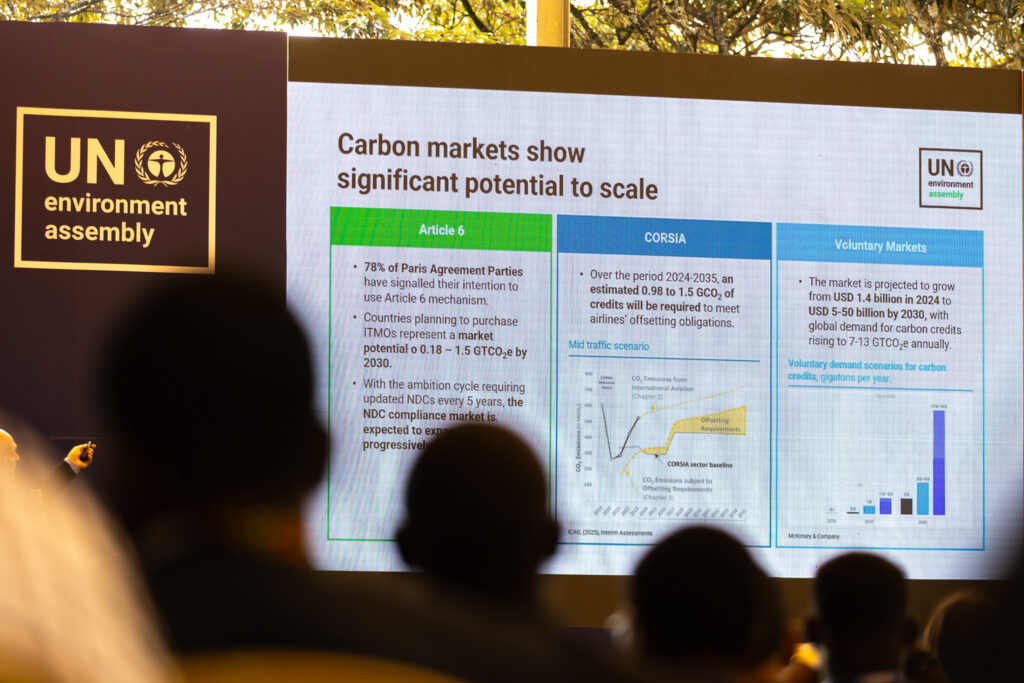

Despite steady growth in carbon markets, Andersen cautioned that the sector must not expand without proper safeguards.

“As the carbon markets are set to grow fast, we have to prioritize governance, transparency and high integrity,” she said. She added that access must be broadened for countries that currently struggle to enter the market.

She pointed to recent developments as a foundation for progress. Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement is now fully operational, enabling high-integrity, country-to-country carbon transactions.

Article 6.4 has also advanced through stronger mechanisms for transparency and supervision. Several countries are additionally calling for simpler rules and lower transaction costs to accelerate implementation. Brazil’s push to harmonize carbon standards, Andersen said, could help reduce the fragmentation that continues to hinder many nations.

Still, hurdles remain. Nature-based credits under Article 6.4 may take years to materialize, and many developing countries continue to question why carbon finance remains out of reach.

Without real access for vulnerable nations, she warned, the system risks benefiting only a few. Integrity must be strengthened, she said, but simplification must ensure inclusion.

Voluntary carbon market still faces trust deficit

Andrea Abrahams, who leads the International Emissions Trading Association’s work on the Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM), echoed concerns about market credibility.

She said that while 2021 brought strong momentum, innovation and new entrants, the sector was soon hit by intense scrutiny over credit quality.

“Everything looked like the market was going to grow significantly,” she said, but challenges emerged just as quickly.

Supply-side concerns and questions about the reliability of credits created uncertainty. “If buyers can’t be really sure that the credit represents one ton of carbon removed or avoided, then you have a problem,” she noted, particularly when such credits are used to offset emissions.

The voluntary market’s highly fragmented structure, thousands of projects across multiple countries using differing methodologies compounded the issue.

One poorly designed project, Abrahams said, could trigger fears that the entire market was unreliable, with a “numbing effect” on confidence. Demand fell sharply as a result, causing further instability.

Corporate buyers, who drive most voluntary market demand, have become increasingly cautious due to reputational and legal risks. Abrahams said many companies hesitate to participate even when acting with integrity, fearing lawsuits or allegations of greenwashing.

She argued that the market requires a regulatory “safe harbour” that allows buyers to participate responsibly, supported by mechanisms that clarify how claims can be made.

For the carbon market to thrive, Abrahams said two conditions must be met: credible supply and secure demand. While new standards such as those from the Integrity Council for the VCM and labels like CORSIA and CCT are improving supply integrity, she stressed that more effort is needed to strengthen demand. “That’s where the finance is coming from, so we have to get that part right,” she said.

Africa looks to carbon markets as finance gaps expand

Africa’s renewed push into carbon markets is driven by necessity, said Dr Olufunso Somorin, Regional Climate Head at the African Development Bank.

The continent needs about $286 billion a year to meet its climate goals but receives only $52 billion, covering just 10 percent of its requirements. Private climate finance to Africa stands at only 18 percent, well below the global average of nearly 50 percent.

“This is why Africa is all of a sudden interested in carbon markets,” he said, noting that the continent currently taps only two percent of its potential in voluntary and compliance markets. “It would be a missed opportunity for Africa not to be part of it.”

To build a strong, high-integrity carbon market, Somorin said countries need solid policy frameworks, institutional capacity, digital systems and readiness tools.

He highlighted three African Development Bank initiatives aimed at supporting this transformation: a new African carbon market coalition focused on policies and capacity building; blended-finance experimentation to attract private capital; and the Africa Carbon Support Facility, a $100 million programme that provides both upstream readiness support and downstream investment for project developers.

“We’re learning by doing,” he said. “And we hope that soon, we’ll look back and see real progress across the continent.”

Tanzania shows the potential of blended finance

Tanzania is emerging as a practical example of how blended finance can expand access to carbon markets in least-developed and climate-vulnerable economies.

According to Omon Ukpoma-Olaiya, Regional Investment Team Lead at the UN Capital Development Fund (UNCDF), blended finance provides a structured approach that lowers risks and enables participation in markets that would otherwise remain out of reach.

“We see blended finance as a gateway where carbon market participation can leverage new opportunities,” she said.

UNCDF’s model combines grant resources with return-seeking investment, helping reduce risks for investors in environments with high uncertainty and small transaction sizes.

In Tanzania, UNCDF is applying the approach through its clean-cooking programme. “We worked with the government to support close to a hundred companies with upfront capital,” she said.

These companies developed clean-cooking solutions that have already shown significant reductions in emissions. The next step is to help firms monetize these reductions by turning them into carbon credits that can strengthen their revenue and resilience.

Ukpoma-Olaiya said blended finance is particularly important for small and medium enterprises that may lack capital to participate in carbon trading. It ensures that markets often excluded from carbon finance can benefit from emerging opportunities.

Investors want predictability

Speaking about what carbon market investors need, Luke Cillie, a Tax Associate at Ernst & Young, said the sector depends heavily on reliability and predictability. When uncertainty is high, he said, investment becomes difficult.

“All it takes is one bad apple in a basket of a hundred good apples,” he warned, underscoring the need for clear standards and strong oversight. He added that carbon market rules must work domestically and comply with international requirements to maintain trust.