By Habitat Reporter

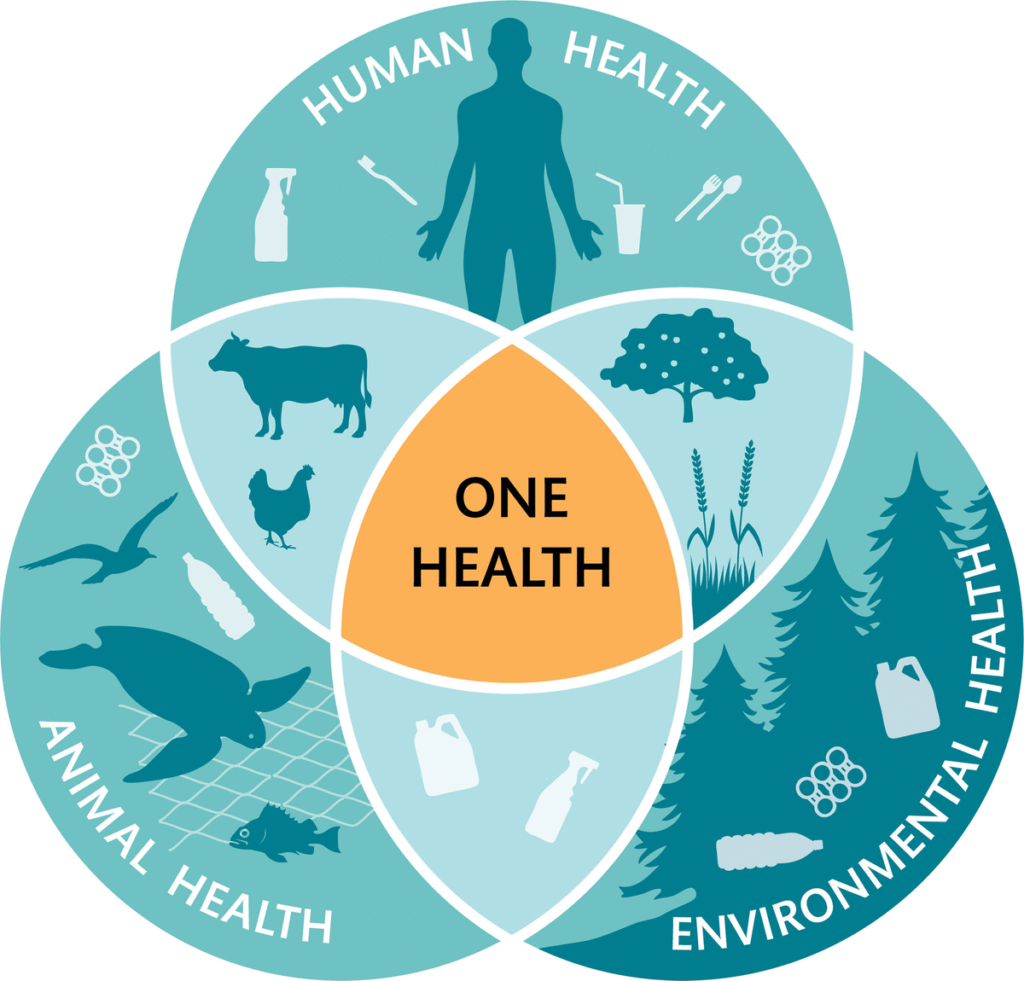

Geneva, Switzerland. As governments negotiate a historic treaty to end plastic pollution, scientists are sounding the alarm over the growing health impacts of plastics — warning that the damage may already be generational.

A report by the Minderoo Foundation and the University of Maryland, featured in the Lancet Countdown on Health and Plastics last week, reveals that the burden falls heaviest on developing countries and vulnerable populations, particularly children.

According to the findings, the world loses an estimated $1.5 trillion annually (Sh193.8 trillion) to diseases linked to plastic use and exposure. Early-life exposure to plastics and their chemicals is associated with increased risks of miscarriage, prematurity, stillbirth, low birth weight, reproductive organ defects, neurodevelopmental impairment, impaired lung growth, and even childhood cancer.

Professor Sarah Dunlop, Director of Plastics and Human Health at the Minderoo Foundation, told The Guardian during the ongoing negotiations in Geneva that exposure begins as early as the womb. Researchers detected plastic-related chemicals in amniotic fluid, cord blood, and even infant urine.

The study focused on three well-known chemicals: BPA (used in food containers and linings), DEHP (a plasticizer), and PBDEs (flame retardants). It examined their links to cardiovascular disease, premature death, and loss of IQ in children.

African countries — including Tanzania, Uganda, and Cameroon — were among 39 nations where human biomonitoring detected evidence of exposure. “The health impacts are serious and, in some cases, irreversible,” Dunlop said.

“Plastic is not just an environmental problem. It’s a human health emergency — and Africa is on the frontlines,” she stressed.

A separate study cited in the report found that prenatal exposure to BPA could increase the risk of an autism diagnosis six-fold in genetically predisposed boys.

“This is no longer about correlation. We’re beginning to understand causation. And with that comes responsibility,” Dunlop noted.

She warned that early-life exposure to plastics may result in reduced fertility and higher risks of cancer, diabetes, and heart-related diseases in adulthood.

Africa’s Unseen Burden

While plastic exposure is a global problem, African nations face disproportionate risks due to weak waste management systems and the widespread open burning of plastic waste — a common practice in informal recycling sectors.

“When plastics like PVC are burned — whether on the roadside or in landfills — they release dioxins, some of the most toxic chemicals known to science. These are linked to cancer, reproductive harm, and birth defects,” Dunlop explained.

There Are Alternatives — But at a Cost

Dunlop said safer alternatives are possible but remain expensive. One promising option is polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA), a biodegradable and non-toxic plastic produced by bacteria using waste products such as sugarcane residues or food scraps. PHAs break down like compost and do not release microplastics or harmful chemicals.

“The challenge is cost. PHA is currently about ten times more expensive than petrochemical plastics. But that’s only because we’re not paying the true cost of the damage caused by conventional plastics,” she argued.

She added that if health and environmental costs were factored in, fossil fuel-based plastics would be far more expensive than their greener alternatives.

A Treaty With Health at Its Heart

Dunlop insists that the upcoming treaty must reflect the latest science and include flexible mechanisms to adapt as new evidence emerges. It should prioritise protecting vulnerable groups — not only children but also pregnant women, who can pass chemical exposures to unborn babies.

“We need to stop seeing plastics as just a waste issue. From production to disposal, it’s a chemical health crisis,” she said.